- Home

- Ben Stubbs

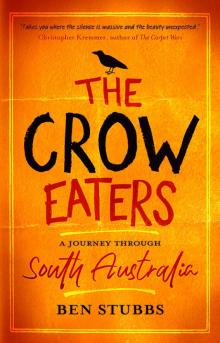

The Crow Eaters

The Crow Eaters Read online

BEN STUBBS is a senior lecturer in journalism and writing at the University of South Australia. He worked as a journalist and travel writer for 15 years in Australia and overseas for publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Toronto Star, The Sydney Morning Herald and Rough Guides. He has also published two books since 2012 on travel writing and immersive journalism. He lives in the Adelaide Hills.

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

© Ben Stubbs 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN: 9781742236315 (paperback)

9781742244563 (ebook)

9781742249032 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Luke Causby, Blue Cork

Cover image (crow) gettyimages, bulentgultek

Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander readers should be aware that this book may contain mention of people who have died.

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MAPS

1 A BEGINNING

2 WHITE MAN IN A HOLE

3 MARALINGA

4 WHAT LIES BENEATH

5 THE CAMEL MEN OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA

6 GREAT WHITE

7 THE CROW EATERS

8 WORKING THE LINE

9 A STEP BACK

10 THE LONELY NORTH

11 BOOM AND BUST

12 THE RIVER

13 THE QUEEN’S TOWN

14 ADELAIDE

READING LIST

For Laura, Dante and Frankie and the place we call home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I never intended to write this book. The more time I spent in South Australia, though, the more my curiosity to look closer at the place where I live, persisted. Thank you to the many people who encouraged, advised, talked with me and revealed their own stories of South Australia during my time on the road.

Firstly, thank you to Arts South Australia for recognising the potential in my idea and helping me fund the early trips. To my agent Lyn Tranter for her relentless drive throughout the process, to Fiona Sim for her astute editing and to Phillipa McGuinness and Paul O’Beirne at NewSouth for their support, expert advice and for making me feel part of the family from the first day.

In South Australia I’m grateful for the assistance of many people who gave me a place to stay, some of their time or shared a ride with me along the way: Sam Vincent, Debby Clee, Wayne Borrett, Robin Matthews, Liz Reed, Pamela Rajkowski, Andrew Fox, Paul Polacco, the May family, Al Walton and his family, Cherie Gerlach, Nick McIntyre, Jill Freear, Sarah Diekman, Dave Willson, Arthur Coulthard, Ross and Jane Fargher, Kate Hannon, Trevor Wright, Kym and Jo Fort, Sam Stewart, Dave Natrass, Ruth Roberts, ‘Clacker’ John, Mary and Bill, Royce Kurmelovs, Glenn Docherty, Antonio Caruso, Merrilyn Ades, Ron Hoenig, Klee Beneviste and Sheikh Haitham.

In particular, I’d like to acknowledge the support of Ian Richards – not only for reading the manuscript and giving me sage advice when I needed it, but also for imploring me to stick with it when the going got tough. To my parents, Phil and Sue, for their continuing encouragement as always, and finally to Laura, for everything said and unsaid along the way, I couldn’t do it without you by my side.

An early version of Chapter 3, ‘Maralinga’, was published in The New York Times. And an edited version of Chapter 5, ‘The Camel men of South Australia’, appeared in the Griffith Review.

CHAPTER 1

A BEGINNING

O ‘Arcadian Adelaide,’ may you improve – may your people prosper, and be happy, in order that they may remain in their own Village, and inflict themselves less on the outside world.

Thistle Anderson, Arcadian Adelaide (1905)

South Australia often sits happily on the periphery of Australian understanding – out of sight and out of mind. Outsiders are often aware that the settlers here weren’t convicts, that eight bodies were found in barrels in a Snowtown bank vault and that the wine is nice, though for a state that is larger in area than all but 30 countries in the world – nearly twice the size of Spain and three times larger than Italy – it is confounding that so many of South Australia’s other stories remain on the edges.

The idea that South Australia is a place not worth one’s time goes back to the early 20th century. Thistle Anderson was a local poet, actor and satirist when she wrote a 40-page pamphlet, Arcadian Adelaide, to shine a light on the dullness of South Australia. She remarked that in 1905 the world was in the tumultuous grip of a Russian revolution, the Russo-Japanese war which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, the Moroccan crisis which pre-empted the First World War, and the discovery of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, yet the only notable occurrence in Adelaide, according to the state’s yearbook, was the opening of South Australia’s first kindergarten. Thistle was the nom de plume of Mrs Herbert Fisher of North Adelaide, who had had enough of the nothingness of the ‘City of Churches’. So this educated woman, originally from Scotland, took the genteel city to task for its inability to shift the status quo, to get some blood pumping in its veins. She chastised Adelaide and wrote that it was a place only ‘remarkable for drunks’ and plain women, yet she also apolo-gised to the broader public for the poor quality of the state’s wine at the time. Thistle wondered if the main industry in Adelaide was ‘child-bearing’, though she was also curious whether the ‘Almighty Himself would approve of the perpetuation of some of the Village family-trees’ in Adelaide’s suburbs that were becoming alarmingly inbred. She thought the best thing about Adelaide was that ‘you could buy a ticket to Melbourne at the railway station’ to get out as quickly as you could.

Thistle lit something of a fire under the backsides of the previously polite Adelaideans. She was scorned from all sides; critics told her to ‘quit books for babies’ and that a little knowledge was a dangerous thing, especially for a woman. The broadside Thistle launched at the South Australian public also brought widespread praise for her wit and ‘sledge-hammer like force’ in waking up people. Shortly after her pamphlet’s release, Thistle left Adelaide for San Francisco and she never returned, though what her writing did was to get people from within South Australia and around the country to take notice of Adelaide, to talk about the state, to defend the city and to offer their own stories and experiences to show it as something more than a dull capital of booze and large families.

South Australia has once again become buried in hysteria and rhetoric. It is time to explore the state that looks like an apologetic frown on the southern edge of the Australian mainland to see what it is like beyond the clichés and the media scorn for wind energy, unemployment and out-of-touch politicians.

South Australia has become an enigma. It is either the butt of jokes or it’s treated as some tourism utopia of wine and wildlife, as seen with recent articles from The New York Times and Lonely Planet naming the state as one of the best places in the world to visit. What is there here beyond these broad strokes? There’s a big space of grey in the middle of its nearly one mi

llion square kilometres.

With the ease of travel it is little wonder that South Australia, and South Australians are often overlooked. You can be in a yurt on the Mongolian steppe within two days if you really want to be; you could be slurping gelato on the Amalfi Coast with minimal fuss by the weekend; or you could even be in Bali before breakfast tomorrow.

Despite this ease, the notion of travel is changing. An era of looking closer is approaching, where travellers will begin to look around them and below them, rather than always afar. With the precariousness of Donald Trump’s administration forcing even the most placid and mainstream travellers to re-think their need to go abroad, the time to look beneath our toes is upon us.

The idea of looking closer is something that I had never considered seriously until now. My curiosity was not provoked by Donald Trump’s absurdities, but by a book I picked up about a man travelling around his bedroom in the late 18th century. Xavier de Maistre wrote A Journey Around My Room while being imprisoned in his room for six weeks after he was caught fighting a duel in Turin in 1790. Rather than sit and sulk, he decided to write a travel book about everything in his room. He observed his surroundings through a different lens to give the reader an alternative perspective on what travelling could be and that there are things all around us that we don’t normally pay attention to.

What a comfort this new mode will be to the sick; they need not fear bleak winds or change of weather. And what a thing, too, it will be for cowards; they will be safe from pitfalls and quagmires. Thousands who hitherto did not dare, others who were not able, and others to whom it never occurred to think of such a thing as going on a journey, will make up their minds to follow my example.

I have also noticed that there is something strange about many of the South Australians I have met since arriving. They have a secretive pride about their state and the stories within it. It seems to me that many people here are protective of their own histories and it’s not until you stop and look a little closer and talk to people that you begin to understand the storylines which connect the towns and the ranges like curves on a topographical map. You don’t need to travel 10 000 kilometres to find a story; it can be right here, literally buried below your feet.

The history of this place was in my hands, hiding just beneath the soil. I pulled up a curved lip of clay from beneath a tangle of old roots and wriggling worms; it was the edge of a brick. Over the next few days, gardening in my backyard, I pulled up more than 30 shards of old bricks and pottery from the earth. I moved to Littlehampton, a tiny village in the Adelaide Hills, five years ago from the eastern states. I’m an outsider here, though it’s become my home and a place I’m curious to learn more about. Littlehampton was once a busy community with a railway station, abattoir and meat processing plant, a brewery, plantations and a travellers’ pub. On the corner of my street there was once a brick factory, Coppin Brothers, which began in the 1850s, using the rich clay soil beneath the hills to make bricks for the people of Mount Barker and to provide competition for the Littlehampton Brickworks, which still has a yard full of fired bricks and a kiln chimney and could once house 50 000 bricks. It is from the clay deposits on the corner of my street that many of Adelaide’s early houses were built.

Many years have passed since Coppin Brothers closed down. Before my family arrived here, an old lady who lived in a cottage surrounded by overgrown gardens and blue-painted walls owned our block. Within her overgrown gardens the history of the brickworks and the story of my street was gradually swallowed by soil and tree roots.

In Bruce Chatwin’s book In Patagonia, his journey to the south of South America is prompted by a piece of animal skin he finds in his grandmother’s cabinet – it was supposedly found by a relative of his who travelled along the edges of South America as an early explorer. As I dig up flecks of clay and brick from my own backyard it prompts me to want to understand my surroundings – to do what de Maistre did in his bedroom and Chatwin did with the piece of skin, and to look closer. There is nothing particularly remarkable about the discovery of a few old bricks, though it made me stop and think. What are the other stories of South Australia lying beneath the surface waiting to be excavated?

Like the spokes on a bicycle wheel, I will venture out from my home in all directions around the state, in cars, planes and boats; using feet, flippers, torches and paddles to discover more about the place I live. I’m not interested in a guidebook’s flippant coverage either. This is something different. Rather than hope to tread each inch of the state I will be guided by the stories I discover, the people I meet and the questions I’ve been storing about South Australia to act as my compass for my travels ahead.

CHAPTER 2

WHITE MAN IN A HOLE

The phrase ‘to die of thirst’ has little meaning to most people in modern Australia. Except in the desert. When extreme dehydration sets in, it starts with dizziness, headaches and cramps. Then your heart starts beating faster as your body works harder to function; a fever will develop and then, as the sun and the air suck the sweat and saliva from your body, your face will turn grey while the blood vessels under your skin shut down. The water acting as a cushion for your spinal cord will dry out, your kidneys will fail and that will be it. All prevented by something as simple as a glass of water.

Thirst is one of the defining characteristics of the arid land above Goyder’s Line in South Australia – the invisible line created by George Goyder in 1865 to identify a reliable rainfall marker across the state. Many men made their fortunes selling water to miners and explorers in the early days and, even now, people still die of thirst here if they’re caught in the hot, baking sun without a drink. As I drive north, past the burned earth and shimmering heat on the road, it’s all I can think about.

I leave Adelaide in the early morning. It is full summer and the week after Christmas. The roads are quiet so it’s easier to see the mirages levitating off the black surface as I creep northwards. The heat and access to water have defined much of the north. I want to experience it at its peak.

In the past, the hotels, inns and watering holes along the spine of the state were crucial for explorers, drovers, cameleers and others moving through on exploratory missions. It is a similar necessity now which forces travellers to plan their routes and watch their gauges before filling and refilling their vehicles once, twice or sometimes even three times in a day along the Stuart Highway which barrels along all the way to Darwin at the top of Australia.

A few hours north of Port Augusta, at Spud’s Roadhouse in Pimba, I see the daily special, ‘Beef Karma’, scrawled in chalk on a noticeboard out the front. It’s now 45°C outside. I don’t think the misspelling is accidental, though all I buy is petrol and I continue from the roadhouse 8 kilometres to Woomera along the Arcoona Plateau.

The town looks apocalyptic in the midday heat. The brick houses are shuttered. The grass is burned and yellow. A solitary boy weaves along the main street on his BMX, as if surveying the town, post-zombie invasion, for survivors. There are basketball courts, a theatre, a wellstocked supermarket and visitors’ centre, though they are all deserted. ‘It’s almost like you are living in another world, just as though you had been shot off in a spaceship and let down on some strange planet where men had never been before’ wrote Ivan Southall in Woomera.

Woomera is Kokatha country; there are still rock engravings within an hour’s walk of many of the campsites around the area and it is suggested that there were once many ceremonial sites around the cane grass swamps here, which could hold rainfall and sustain life.

On first approach, Woomera looks like an abandoned ‘Thunderbirds’ set. There are discarded rockets, planes and missile trackers repainted and displayed in the local park as if production of the 1960s puppet show simply stopped one day and the puppets upped and left the set with their rockets still waiting to launch.

The coolest place in town is the air-conditioned museum. Inside, grainy video footage tells the story of the rocket range here.

It starts with stories of the Germans firing 1200 V2 rockets that travelled at the speed of sound across the English Channel during the Second Word War. I sit through stock footage of Winston Churchill and the explanation about these rockets motivating the British to find an area to begin their own rocket construction and testing program.

The modern history of Woomera started in 1946, when the British and Australian governments decided that a rocket testing range would be established in northern South Australia. The task of finding the right spot was left up to Len Beadell, regarded by many as one of the last great explorers of the Australian centre. He was an army surveyor who mapped and charted much of Central Australia, opening up 2.5 million square kilometres of the outback, including the 6500 kilometres of roads in Central Australia he constructed with his Gunbarrel Road construction crew in the 1960s.

In the early days of Woomera, the Kokatha Aboriginal people lived within a few hundred kilometres’ radius of the settlement and were managed by solitary Native Patrol Officers in LandCruisers. Unsurprisingly, the rights of the Aboriginal people were never seriously considered and many were resettled to the north or south with other tribes and without any consultation.

After returning from a year in the Northern Territory, Beadell was asked by an English colonel to find a suitable spot for ‘some sort of rocket range’, as he put it. Beadell told the colonel he had a pocket of land in mind larger than Gloucester in the UK, where the colonel was from. He set about surveying the Woomera site, agreeing that it was far enough away from Port Augusta to allow ‘any stray, off-course missiles to be destroyed in mid-air by radio before endangering any civilization’.

As the rocket program gained momentum, it coincided with the early stages of the Cold War, so despite there being little but hot, dusty plains and dry salt lakes in northern South Australia, the threat of espionage kept security tight on the place that was named after the Aboriginal words Miru (woomera) and Kulara (spear), signifying the force of the Indigenous warrior’s throw when using the two together while hunting.

The Crow Eaters

The Crow Eaters